Rinco

From information supplied by Jack Clarke and Fred Frost

Company records reveal that Rinco, a process developed in Switzerland, was introduced at the Sun with the start of Farmers Weekly, a publication on a tighter than average schedule. The technique, which could be used only for monochrome pages, permitted pictures and type matter to be laid and etched as one operation, cutting cylinder processing time in half – to five hours between passing for press and being on the machine. For Farmers Weekly, this meant a significant reduction in time between receipt of the latest agricultural commodity prices for the issue and starting to print the journal.

The Process (as described by Jack Clarke)

Rinco was a process for quickly making inexpensive negatives without using camera or darkroom. It was specifically designed to convert a letterpress surface into a paper negative for the gravure process. Rinco seems to have been adopted in the UK only by the Sun in Watford and Bemrose in Liverpool.

Sun’s Rinco Proofing department employed four or five journeymen plus the same number of assistants (NATSOPAs, later SOGATs) on each of three shifts. Workers in this department originally wore standard brown boiler suits, but since they worked with white ink and white powder all the time, they decided at some point to switch to white overalls, which gave them the additional bonus of being immediately identifiable throughout the works as Rinco men.

How did Rinco work? Metal formes of type (one forme per page) were brought by a compositor from the Composition department. They were placed, each in turn, on the bed of a Wharfedale press and locked into position. White ink was used, and the forme’s image was printed onto a special light-weight but very hard paper, its upper surface coated a deep, glossy black. The printed result was checked for evenness of colour across the sheet. If flaws were found, a small make-ready was done (to build up low areas of the forme, for instance) and the page was re-run until an acceptable image was obtained. As a precaution, two good impressions were always produced of every page.

The printed image on the black paper was greyish in tone and had to be made whiter. At a table under extractor fans, a gritty white powder was tipped into a tray and a small amount scooped up and evenly cast over the freshly printed sheet to cover the inked area. Surplus powder was tapped off and the remaining powder gently rubbed into the ink with a large wad of cotton-wool. This process was repeated, the page was carefully wiped clean of all loose powder, and the result was checked with a linen tester [a strong magnifying glass] to make certain that the type was white all over and ‘pin-dot’ sharp. Considerable skill was needed for this work. Too much ink would make the type edges whiskery after the powder had been added, uneven powder coverage would leave the type uneven in brightness, too heavy a touch risked smudging the tacky ink, and rough or careless handling of the Rinco paper could cause the black surface to become marred or creased, ruining the image.

Bob Hibbert, supervisor, prints a white image onto a sheet of Rinco paper. Behind him are extractor units to clean the air of Rinco powder. (Photo supplied by Jack Clarke)

The final product – a delicate paper negative – was, when properly produced, as sharp as a film negative, and its creation would have taken, on average, about ten minutes from start to finish.

The pairs of pages were then carefully placed, face to face, under and over an interleaving sheet, and when the whole job was completed, were taken (again by an assistant) to a conveyor belt that linked the Rinco and Process departments. This was the last the Rinco men saw of the pages unless a problem was discovered. After the publication date, the Rinco negatives were filed for a safe period, then discarded or burnt, and the formes were taken apart in an area of the Composition department called “diss alley” (“diss” for distribution). Headline and display type, as well as certain decorative blocks, were returned to their home cases in the Composition department, and the rest of the metal was melted down for reuse on the Monotype and Linotype machines.

Rinco remained an integral part of the Sun’s production process for decades, but was rendered obsolete in 1980 when the company switched to photocomposition.

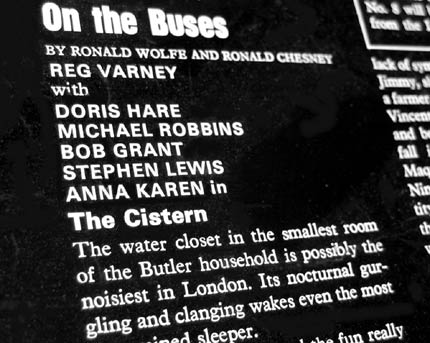

Example of a Rinco proof (still in good shape after 35 years) from the Anglia edition of TVTimes for Friday, January 9, 1970. The paper negs of the pictures were pasted onto the Rinco proof in the Process department prior to the making of the film positive. (Sample courtesy of Basil Boden)

Further Information (as supplied by Fred Frost)

The Rinco process was sold or licenced to Sun by Ringier in Zofingen, Switzerland. The special black-coated paper was initially supplied from Switzerland by a company called Typon, photographic suppliers to the graphic arts trade. We simply knew it as “Rinco paper” and it was probably quite expensive, since it was made to a specification that would always generate perfectly clear non-image areas when shot to positive. I believe that at some point Typon discontinued it and we sourced it for a short time from Ilford in the UK.

I recall two paper sizes to match the single and double spreads of the largest magazine pages we printed. The proofs were transported in the empty process film boxes that matched the film size formats for the fixed same-size cameras that were used for direct-tone positive-making from the planned Rinco negs.

The powder was a pigment derived from aluminium. Its grittiness is thought to have been caused by the distributing agent used to disperse the very fine pigment across the tacky inked text proof. The aluminium developed an oxide film that would make it appear a little less than pure white, so that when the text and negative pictures on a page were photographed to film positive, the density of the text would equate to the darkest shadows of the pictures. This enabled controlled conditions when etching text and pictures together, avoiding destruction of the essential screen walls in the text.

Excess powder was retained and reused. The actual text, once dusted, was very delicate, and when I was a ‘boy’ (my first job at the Sun was to return the planned Rinco pages and pictures, together with the customers’ layouts, from the Readers to the Rinco planners in the Process department), I recall being reprimanded by the Rinco planning manager if I left the layout on top of the related Rinco proof when I made my deliveries. Within the Process department, Planning was one of the trades that required a 5-year apprenticeship. The work involved the assembly of the graphics, linework, and text of each page for the Studio to photograph to positive, and then the imposition of all these pages, now film positives, using photographic masks, etc. A reader confirmed, by referring to a page-imposition layout, that all pages were correctly positioned, and then the imposed pages could go to cylinder-making.

STEPS IN THE PROCESS

Origination• Job enters production (job profile sent to costing and charging).

• Customer copy and layouts to Composition Dept., photos, line art, and copy of layouts to Studio.

Composition Dept.

• Type (lino, mono, and/or hand) is set to

match customer-supplied copy and layouts.

• Readers proofread galley proofs of

type.

• Comps make up type into pages, following

customer-supplied layouts.

• Readers check

corrections, position of type, and accuracy of space left for

pictures and other graphic elements.

• Proof of made-up pages to customer for

approval.

• Corrected type formes delivered to Rinco

Proofing.

Studio

• All photos and customer-supplied line

work received.

• Continuous-tone bromide paper negatives

made to size, following copy of customer layout.

• Negatives delivered to Rinco planners in

the Process Dept.

Rinco Proofing

• Type formes received from Comps.

• Type of each page printed in white on

Rinco paper (two impressions taken of each).

• Printed images dusted with powder,

cleaned, checked.

• Rinco proofs delivered to Rinco planners

in Process Dept.

Process Dept.

• Planners paste the paper negs of

photo images and linework onto the Rinco proofs, per customer’s layout.

• Results delivered to readers for

checking and approval.

• Approved Rinco pages to Studio.

• Rinco negs shot to same-size film positives.

• Film positives of pages returned to Process planners.

Process Dept.

• Positives planned in position for

cylinder-making.

• Imposed pages checked by readers against

a page-imposition layout.

• Imposed pages delivered to Carbon

Printing and Etching Dept.