The Fire Brigade

by Pat Valentine, with a first-hand account by Sun fireman Peter Walker. Unless otherwise indicated, the photos were also supplied by Peter Walker.

From earliest days, Sun Engraving’s and then Sun Printers’ letterheads always stated “Not responsible for loss by fire.” Fire was always a risk in the plant, especially in the gravure machine room, the ink factory, and some of the process departments, where large quantities of petroleum spirit were handled. As the web moved through a gravure press, friction could cause a static charge to build up on the paper and attempt to earth through the steel fabric of the machine. The danger was always greater in dry conditions. The area where the web came out of the floor was kept damp with wet rags to keep the fire risk down. Later, special bars attracted static from the paper and improved the situation, but until that time, flash fires were frequent. Furthermore, in humid and muggy weather, ink fumes clung to overalls, putting the wearers at risk if a spark should ignite. Workers were rolled in blankets to extinguish flames on their clothes. The presses were kept running during such a flash fire, and might, in fact, be speeded up, as paper is more apt to catch fire (and the fire is more likely to spread) if a press is stopped.

Rembrandt’s was closed for close to a month in 1957 after a serious fire in the Rotary Machine Room. [For details see Rob Clayton’s 1950s entry on the Reminiscences page.] The risk of fire was so great that fire stations were built opposite both the Sun and Odhams factories. Smoking was strictly prohibited in the factory work areas, and fire alarm systems were elaborate. There were also fire extinguishers all over the presses; when a fire started, the crew of that press and those on adjacent presses immediately swarmed over the press with extinguishers to keep the fire from spreading. By the 1960s, any alarm bells that sounded in the buildings automatically sent warnings to the Sun control room and to the Watford fire brigade as well. No fewer than 32 fires were recorded in the Gravure Machine Room in 1964.

Sun had a full-time chief fire officer in F.G. (Fred) Soar, who carried out this duty for 29 years. His 10-man volunteer fire brigade, comprised of machine minders, assistants, and engineers, underwent the same training as the full-time fire-fighters across the street, and its members certainly proved themselves up to the job, both at Sun and in the many district and national competitions in which they participated. The high point came in 1974, at the British Fire Services Association Competition held at Hayling Island, Hampshire, when the Sun team beat out 40 other industrial fire brigades to win top place at the event, setting record times for some events despite very wet weather. At the National Camp in 1977, against 29 brigades, Sun’s team were runners-up, bringing home three first prizes and four seconds.

But the competitions had a serious purpose, as Fred Soar explained in an issue of Sunews. “We run the brigade for the protection of the factory, not for contests. We do competition work only to keep the men on their toes and to familiarise them with their equipment. I’ve no room for anyone who is half-hearted about the job. These lads are keen and competent, and I’m proud of them.” He had reason to be. The Watford Fire Brigade wound up responding to alarms at Sun Printers on a number of occasions over the decades, but in almost every case, Sun’s own brigade were able to bring the fire under control without outside help.

An exception occurred on January 18, 1978, when a fire broke out on a Martini binder in the Finishing Department. The flames were drawn into the paper trim extract trunking, suspended under the ceiling of the Letterpress Department and leading to the shredders. Works firemen were first on the scene and quickly extinguished the fire on the binder, but the fire in the trunking continued to burn and engineers were obliged to remove sections of the trunking in order to get inside to clear out smouldering paper. A fireman from the Herts station, wearing breathing apparatus, managed to enter a section of the trunking situated on the cyclone roof and dealt with smouldering material there. It was the first notable fire at Sun in many years. No permanent damage was caused, although the Letterpress Department got a good dousing and some letterpress machines had to be dried out.

The door (top left) led to the Finishing Dept., where the fire started. Firemen are shown near the two cyclones on the roof. The cyclones were much like vacuum cleaners, sucking trimmings from the stitching lines into large-bore trunking and funneling them to a baling machine at ground level for pick-up by a waste paper contractor. (From the archives)

In the Letterpress Department, mounds of sodden paper trim are cleared away. Sun fireman Peter Walker is shown mopping up the mess; in front of him is warehouseman Harry Fishlock. (From the archives)

Peter Walker has supplied first-hand details on the brigade, as well as many pictures, dating from 1957 to 1986. He writes:

One day in 1957, Freddie Soar, the Chief Fire Officer at the Sun and also in charge of the fire equipment at Rembrandt’s, came over to test the fire alarms and then approached Ron Rooney and myself to see if we would like to join his fire team. We both said we would when he told us that we would get ₤25 as a retainer. Money was money then. That was yearly, by the way. The team used to train after work on a Tuesday evening at the back of the Ink Factory. Before training (not after), a meal at the canteen was provided free if one said ‘Fire Brigade.’ Double egg, sausages, beans, and chips seemed to be the preferred meal and what lovely food they used to provide. After filling our stomachs we would then proceed to the Ink Factory to do a few drills. Being young, we could still move quite fast. Both Ron and I made it into the actual drills, taking over from a couple of the older men.

There were many sorts of drills, wet and dry, for one man or more, up to six. In the spring of 1958 we began entering competitions in different districts – Herts, Surrey, Oxford, Bedford, & Midlands, and did quite well. Prize money went into a pot and was shared at the end of the year. One day, Fred came in and told us that he had applied to go to National Camp and the firm had agreed to let us go. This was for a whole week and wasn’t part of our holiday allowance so that was a bonus. The first year (1958) was at Blackpool in Stanley Park and was all under canvas. I seem to remember 40 teams from different industries all over the country. The initiation for new teams, which came at the end of the week, I vividly remember. In turn we had to lie on a table only in shorts or swimming trunks, in front of a camp ‘doctor’ dressed like a surgeon. He and an assistant then proceeded to smother the ‘patient’ in boot polish and a lot of slops saved during the week by the canteen. So it was eyes shut and mouth closed very tight. They did ask you questions, but the only possible response was either a shake or nod of the head, if one had any sense. From there, one jumped into a big tank of water to get rid of most of the gunge and then was tossed three times into the air on a canvas sheet. Incidentally, we’d done quite well in the drills and surprised a few of the other well-established teams. All the drills were timed electronically. We had a great time and went to camp every year until Maxwell took over. I think 1985 was our last one, and was the end of an era.

When I started, the brigade members were Joe Johnson, Harry Orchard (his son was a manager in the Electricians), Arthur Gostick (Warehouse), Jim Blower, Harold ‘Butch’ Hutchins, Ray Holt (Machine Room), Roy ‘Whiskey’ Miller (Engineers) and Peter Osborne. Later, replacing those who had left, were Maurice Wells, Derek Pangbourne, Dave Carter, Mickey Praide, Barry Langdale, Barry Kempster, Bob Ashley, Bob Manley, Fred Moult, Bob Barton, Dave Haines, Dave ‘Chalky’ White, Herby Walker (no relation), and also a Paul whose surname I’ve forgotten. All of these new men worked in the machine room but were not in the brigade at the same time.

There were some great times with the team, and winning the National Tournament in 1974 at Hayling Island was the icing on the cake, so to speak. I believe that Dennis Gurney, who was at Rembrandt’s when I started, did sterling work when the fire occurred there on the night shift in 1959.

At Hazell’s Sports Ground, 1957. Competing against the Hazell’s Fire Team, Sun’s team won everything – shield as well as money. Back row, l-r: Fred Soar, Peter Walker, Ron Rodney, Joe Johnson, Harry Orchard, Dennis Gurney, and Roy Miller; front row: Arthur Gostick, Harold Hutchins, Peter [?], Ray Holt, and Jim Blower.

National Camp at Paignton, Devon, 1963. Brigade members were all from the Gravure Machine Room, unless otherwise noted. Standing: Jim Blower, Fred Soar (Chief Officer), Roy Miller (Engineers), Harold Hutchins, Dennis Gurney, Maurice Wells, Ron Rooney, Peter Walker; seated: Paul [?] (Letterpress), Joe Johnson, Ray Holt.

National Camp at Paignton, Devon, 1963. Sun’s brigade in dress uniform, with the firm’s grey van in the background. Standing, l-r: Fred Soar, Harold Hutchins, Roy Miller, Dennis Gurney, Ray Holt, Jim Blower, Maurice Wells, Joe Johnson; kneeling: Ron Rooney, Paul [?], Frank [?], Peter Walker. Photo by H.F. Marshall.

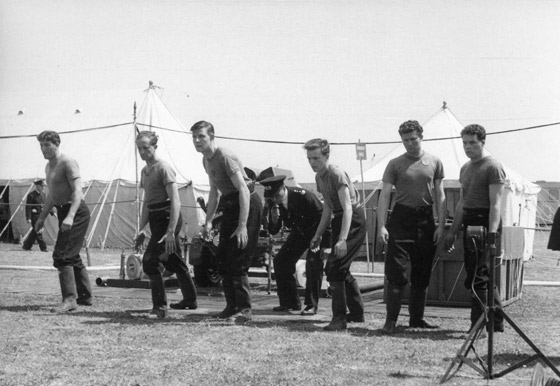

National Camp at Cliftonville, c.1965. Sun's brigade shows its stuff, with Fred Soar on the whistle, Dennis Gurney operating the pump, and Peter Walker set to go for the second part of the drill.

National Camp at Cliftonville, c. 1965. Fred Soar blows the whistle to start the ‘turn-out’ drill. L-r: Dennis Gurney, Harold Hutchins, Jim Blower, Ron Rooney, Peter Walker, and Ray Holt.

Chief Office Fred Soar polishes trophies won by the brigade at the British Fire Services Association’s South Midlands District Championships in July 1969. The brigade’s success at the Hayling Island competitions a few months later would add yet more shields and cups to the collection. Photo by D.A. Markwick. (From the archives)

Sitting around the Dennis Pump on the Sun Sports Ground after winning the 1973 South Midland District competitions and setting two record-breaking times in the major pump drills. Back: Rob Ashley, Ron Rooney, Dennis Gurney; front: Fred Soar, Joe Johnson, Derek Pangbourne, Barry Langdale, Roy Miller, Ray Holt, Dave Carter, Peter Walker, Harold Hutchins. Photo by Graphic Photos Ltd.

Bringing home the prizes, 1974. The Sun brigade unloads its trophies after winning the national championship at Hayling Island. L-r: Dennis Gurney, Bruce Hutchins, Barry Langdale, Ron Rooney, Mickey Praide, Ray Holt, Dave Haines, Dave Carter, Bob Ashley, Derek Pangbourne, Peter Walker, Roy Miller. Taken at the Sun Sports Ground. The van was blue with white writing and an orange sun.

Formal p ortrait of a winning team, 1974.

Showing off their Hayling Island trophies are (left) Peter Walker with his children Andrew and Hayley, and Dennis Gurney with his daughter Denise.

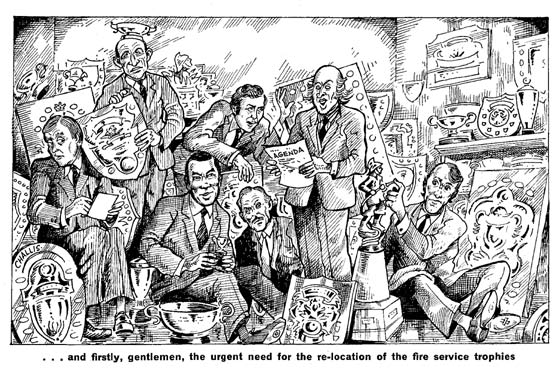

A November 1977 cartoon showing Sun management trying to hold a meeting in the firm’s trophy-laden boardroom. Shown are, l-r, Gerald Mowbray, Charles Brinsden (standing), Paul Harding (sitting), Brian Gurney (standing), Dennis Wells (sitting), Clive Bradley, and Michael Knowles. Cartoon by Challis. (From Sunews)

At Caister, Great Yarmouth, with Ivy Benson, who was appearing there with her renowned All-Girl Band. Undated, but likely late 1970s or early 1980s. Standing, l-r: Fred Soar, Ray Holt, Ivy Benson, Roy Miller, Harold Hutchins, Bob Ashley, Peter Walker, Mickey Praide, Dennis Gurney, Derek Pangbourne; front: Dave Haines, Barry Langdale, Dave Carter, Ron Rooney.

The Sun Brigade with the impressive number of trophies won in 1986. Back, l-r: Roy Miller, Derek Pangbourne, Peter Walker, D. White, Dennis Gurney; front: Mickey Praide, Barry Langdale, Dave Haines, Ray Holt.